Relationship-Building & The Lost Narratives of Women and Minorities in Our Communities

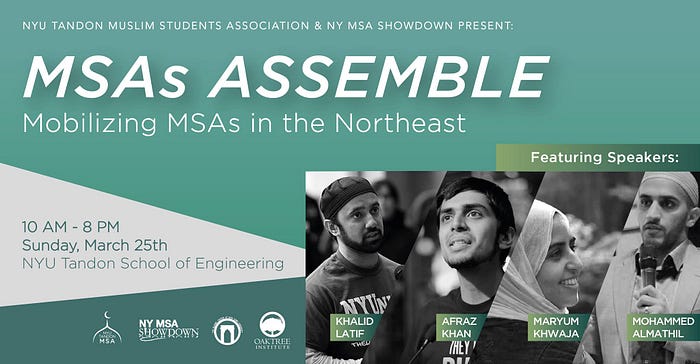

I am humbled to say that, due to an interesting turn of events, I was chosen as one of the main speakers for the MSAs Assemble Summit in which about 15 Muslim Student Associations from across the city and the Northeast gathered together to discuss ways in which they could effectively collaborate with another on projects and programming to make an impact that would extend beyond the boundaries of their respective universities.

The organizers recommended I speak on the power of unity and its importance within our faith tradition. For me, one of the integral components of building out unity within any sort of community or network is actively seeking out and learning the narratives of the individuals around you. It amazes me how, particularly within the Muslim community, our faith tradition prescribes that we stand shoulder-to-shoulder when praying to demonstrate an intimate, physical unity, but oftentimes we fail to expand on that physical bond by building out a relationship with those very people.

In not knowing the narratives of the individuals in our smaller communities, it is difficult, especially as a leader, to build out a unity that encompasses those very same folks. As many of us have experienced, the people who are in the minority in our communities or may not have the necessary platforms for their narratives to be known get easily neglected and left out. To be real, this is oftentimes unfortunately the case with women both in our Muslim communities and also in larger communities, both faith-based and non-faith-based.

One of the stories from the Qur’an I shared in this speech that demonstrates the power of knowing and highlighting individual narratives is the story of Khawla bint Tha’labah (May God be pleased with her). She was amongst the early generation of Muslims during the time of the Prophet (peace be upon him) and was a well-respected individual in her community. She narrates this story in which she discusses the relationship she had with her husband, Aws ibn al-Samit.

Throughout their marriage, Aws ibn al-Samit was mentally and verbally abusive towards Khawlah. One day, a particular issue comes up in which he becomes so angered that he says to her, “you are to me like my mother’s back.” [It sounds a bit strange when translated into English, but this comes from an Arabic phrase that was used by husbands in the pre-Islamic days in Arabia to immediately divorce their wives and that Aws was wrongfully using against his wife, especially given that they had both accepted Islam.] This essentially meant that Aws was no longer going to treat Khawlah like a wife, she would have no rights as a spouse and that he would force her to remain in the house like a prisoner.

The next day, Aws leaves the house and when he returns, he is in a calmer mood than the day before. Ignoring his previous interaction with Khawlah, Aws attempts to get physically intimate with Khawlah and she vehemently rejects him. She argues that there’s no way after having lost his temper and essentially divorcing her that Aws can simply just resume marital relations. Not pleased with her rightful resistance, Aws tries to physically impose himself upon Khawlah. Being younger and more physically able than her husband, Khawlah is able to push Aws away. She immediately then goes to the Messenger of God (peace be upon him) to report to him exactly what happened.

Upon having heard what Khawlah said, the Prophet receives divine revelation from God and an entire chapter of the Qur’an, Chapter 58 (The Pleading Woman), is revealed.

God says in the first verse: God has heard the plea of that woman that has come to you complaining about her husband and she grieves to God. And God hears your dialogue; indeed, God is Hearing and Seeing. [58:1]

The chapter continues by supporting Khawlah and denouncing the divorce practice utilized by the husband.

I shared 3 reflections on the following story and ultimately how it ties back to building unity:

1) The Prophet could have easily provided some words of consolation for Khawlah as well as a ruling on how the situation should be handled between her and her husband, as he did for countless other individuals. However, out of the thousands of interactions the Prophet had with various people, God made it a point to highlight the case of this individual woman who was experiencing domestic abuse. It makes you think how this book, although finite in being only 6,236 verses, dedicates an entire chapter to preserve this woman’s narrative so that it could then be disseminated to the billions of people, both men and women, who would in some way encounter this book and read her story all the way till the end of time.

2) God says that ‘He hears the plea of this woman’ to make it evident that He is always Hearing. 85% of domestic abuse victims within this country are women and the unfortunate reality is that many of us are aware of women both within our families and our communities who have dealt with and are dealing with domestic abuse. I find this story uplifting because I think about the women in my life, a mixture of relatives and community members, who have to continue to deal with abusive relationships while caring for their parents, raising children, and maintaining a household and are not in a position where they can necessarily reach out to someone for help or support. God takes this story as a way to let them know, to let all of us know, that He Hears the complaints, Bears witness to the struggles and ultimately Knows the difficulties experienced by these brave souls. And He will continue to Hear, especially when no one else is there to do so.

3) The ultimate point comes down to this: I ask myself, ‘what’s the wisdom behind God wanting me to know the story of this particular woman in His Book?’ I then have to ask myself, ‘why am I not finding it necessary to know the narrative of this woman?’ In neglecting our sisters within so many of our community spaces (both religious and non-religious), we oftentimes neglect their narratives and experiences, both positive and negative. This is God telling humanity and telling me that as a man, I need to know the story of Khawlah bint Tha’labah. I need to know what she experienced and the pain she endured and how that affected both her and the larger community.

On a larger scale, this is God telling me and us men that we have to be aware of the sisters in our community and make that effort to know their stories, especially when they can become so easily overlooked within the patriarchal society we live in. In the same way that I am not a woman and cannot relate to Khawlah and her story, this is God telling me that beyond knowing the struggles of people I can relate to or associate with, I have to delve deeper in my relationships with individuals in my community with whom I do not share the same ethnicity, faith, gender or the same able-bodied condition.

I can easily live a life in which I never know what it is like to be a woman in an abusive relationship, a Black person in this country or someone who grew up with a hearing impairment. However, if I want to claim that Islam makes up the core of my personal values and beliefs, I have to engage with the Qur’an and it certainly means engaging with narratives that I will never experience but that I am just as much expected to know because they pertain to people with whom I am seeking to build unity; the people I call my brothers and sisters not just in faith, but in humanity.